A Comparative Analysis of Vision-Language Models for Scalable Waste Recognition

01/12/2025

Dec 1 , 2025 read

Why Automation Matters More Than Ever in Waste Management.

The world is facing a growing waste management challenge. As populations expand and economies develop, the amount of municipal solid waste (MSW) produced each year is expected to rise from just over 2 billion tons today to 3.4 billion tons by 2050. Traditional waste systems – built around routine collection, manual sorting, and heavy reliance on landfills – are simply not able to keep up. These outdated practices often lead to overflowing bins, unnecessary emissions from collection vehicles, and serious environmental and public health risks, from water pollution to the spread of disease.

Check this : How Robots Could Save $6+ Billion Worth Of Recyclables A Year | AI In Action

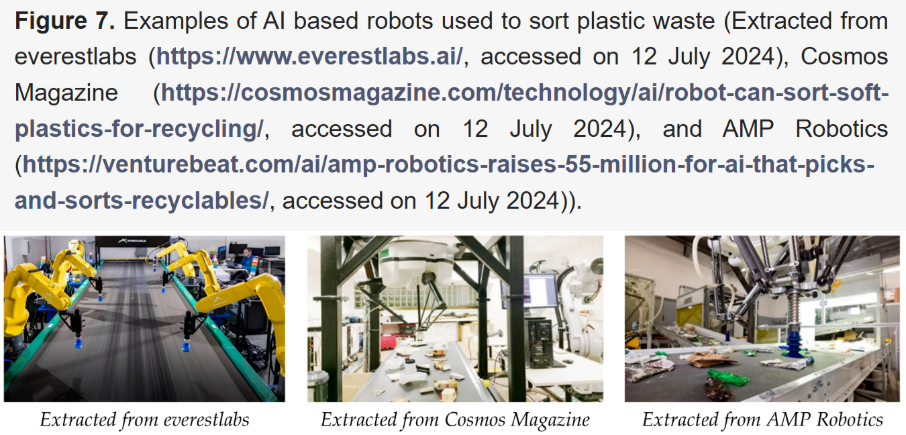

To address these issues, automation is becoming essential, especially in Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs). Robotic sorting systems equipped with advanced sensors can dramatically improve efficiency, reduce operational costs, and protect workers from the hazardous conditions associated with manual sorting. At the heart of these systems lies computer vision (CV), the technology that enables machines to recognize and classify materials on a conveyor belt.

This white paper compares two major computer vision approaches for waste recognition: traditional unimodal (image-only) models and the fast-emerging class of multimodal Vision-Language Models (VLMs). We examine how each approach performs across zero-shot, few-shot, and fully supervised learning settings. Our analysis shows that while traditional models can reach high accuracy, their reliance on large, manually labeled datasets makes them difficult – and expensive – to scale. VLMs, by contrast, offer a compelling path to overcoming these limitations.

We begin by reviewing the conventional computer vision framework and exploring its strengths and constraints.

The Conventional Approach: Unimodal Computer Vision in Waste Classification

Understanding today’s standard computer vision methods is crucial, as these unimodal systems have laid the foundation for automation in waste sorting. For years, they have enabled robots to perform increasingly complex sorting tasks. However, the technical foundations that make these models powerful also introduce challenges that limit their flexibility in the unpredictable environment of an MRF.

Traditional CV models for waste classification are typically built on established deep learning architectures such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) – including widely used variants like ResNet – and more modern Vision Transformers (ViTs) like the Swin Transformer. These models are usually pre-trained on large general-purpose image datasets (e.g., ImageNet) before being fine-tuned on waste-specific images. Another common approach uses Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) combined with feature extraction techniques like color histograms, Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), or Local Binary Patterns (LBP).

When these models are supplied with enough labeled data, they can perform extremely well. Reported benchmarks include:

| Model Architecture | Reported Accuracy |

| ResNet18 (on TrashNet) | 95.87% |

| Swin Transformer (self-curated dataset) | 99.75% |

| Improved MobileNetV2 | 90.7% |

| ANN with Feature Fusion | 91.7% |

Despite strong accuracy, their greatest limitation is the enormous amount of labeled data they require – not only during initial training, but also in ongoing retraining cycles. Real-world waste is far more variable than curated datasets, which means models must frequently be retrained to recognize new, damaged, or contaminated materials. This dependence on continuous annotation and augmentation becomes a major barrier to scalability and cost-effectiveness.

These challenges pave the way for a more flexible and scalable alternative: Vision-Language Models.

An Emerging Paradigm: Vision-Language Models (VLMs)

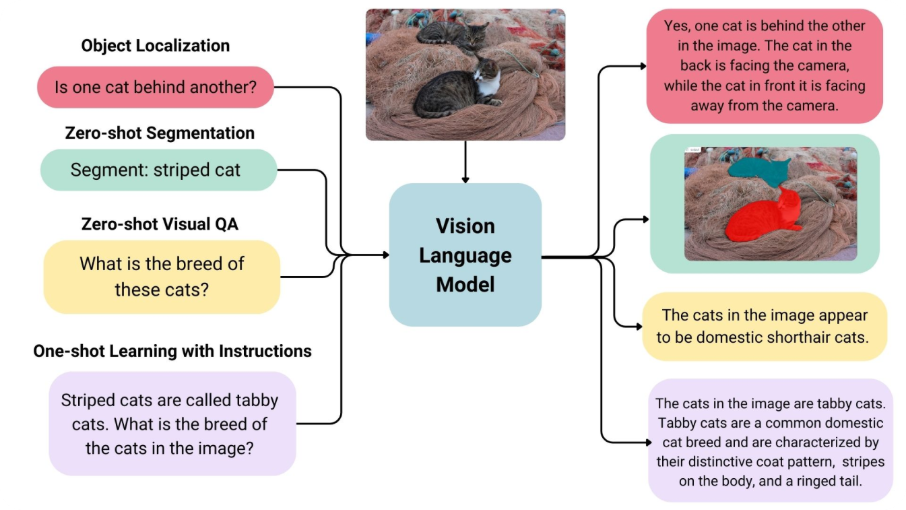

Vision-Language Models represent a significant shift in how machines understand visual information. Instead of relying solely on images, VLMs learn by connecting visual content with natural language descriptions. This multimodal training allows them to recognize objects with impressive flexibility – even without any task-specific training data.

VLMs are built from two main components:

- A visual encoder (often a ViT or CNN) that converts an image into a semantic embedding.

- A text encoder (typically a transformer) that transforms natural language descriptions into corresponding text embeddings.

Using contrastive learning on massive datasets of image–text pairs, models like CLIP, OpenCLIP, and MetaCLIP learn to map related images and text to similar positions in a shared embedding space.

The Power of Zero-Shot Learning

The defining strength of VLMs is their ability to perform zero-shot classification – recognizing categories they’ve never been specifically trained on, using only natural language prompts. This process works by:

- Encoding an image of a waste item.

- Encoding a set of text prompts (e.g., “a photo of a cardboard box,” “a picture of a plastic bottle”).

- Comparing the image embedding to each text embedding.

- Selecting the category with the highest similarity score.

This entirely removes the need for labeled waste datasets and allows the model to classify items right out of the box.

Efficient Supervised Learning with Minimal Data

When labeled data is available, VLMs still shine. Instead of retraining an entire model, only a lightweight linear classifier needs to be trained on the image embeddings. This is far more efficient, both computationally and energetically, than training or fine-tuning a conventional model.

Comparative Performance: Accuracy, Speed, and Scalability

For any MRF considering new sorting technology, performance matters. This section summarizes how VLMs compare in terms of accuracy, learning efficiency, and inference speed.

Strong Zero-Shot Results Without Any Waste-Specific Training

In testing on a multi-class waste dataset, models like OpenCLIP (ViT L/14-2B) achieved an impressive 82.71% zero-shot accuracy – all without seeing a single labeled waste image. Notably, this zero-shot accuracy often exceeded that of models trained with 10 labeled samples per class, demonstrating how powerful text prompts can be compared to small training sets.

This gives facilities an immediate, reliable baseline for classifying new or uncommon waste types.

Fast Learning and High Accuracy in Few-Shot and Fully Supervised Settings

When training data is available, VLMs learn quickly. Accuracy improves sharply from 1 to about 15 images per class, then gradually plateaus – showing strong generalization from very small datasets. In fully supervised scenarios, top-performing models such as OpenCLIP reached 97.18% accuracy, competitive with state-of-the-art conventional models but with far lower training cost.

Real-Time Speed for Industrial Deployment

Waste sorting is fast-paced, and inference speed is critical. A Pareto analysis revealed that although some models (e.g., MetaCLIP) achieve higher accuracy, their slower inference makes them unsuitable for real-time use. OpenCLIP (ViT L/14-2B) emerged as the optimal model, offering:

- 3.79 ms per image

- ~263 FPS, well above the 30–60 FPS needed for real-time sorting

This makes it viable for high-speed industrial environments.

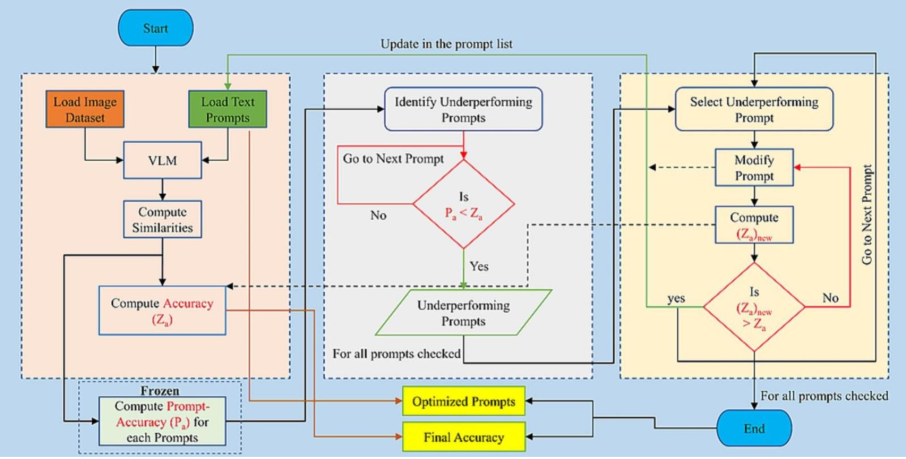

Enhancing Performance Through Prompt Engineering

Prompt engineering provides a low-cost, highly effective way to improve VLM performance. By refining the text prompts used for classification, operators can significantly boost accuracy without retraining the model.

The process is systematic:

- Identify weak prompts by assessing individual prompt accuracy.

- Iteratively refine them to improve clarity and specificity.

For instance, “broken pieces of glass” might be too vague, while “a picture of a glass jar and beer bottles” better reflects what appears on waste conveyor belts.

Applied to OpenCLIP, this technique raised zero-shot accuracy from 82.71% to 90.48% – a nearly 8-point gain achieved entirely through text editing.

Figure : Prompt optimization flow chart

However, prompt engineering must be done carefully. Improving one prompt can sometimes reduce the accuracy of others, making the process a balancing act that requires iteration and thoughtful evaluation.

Datasets

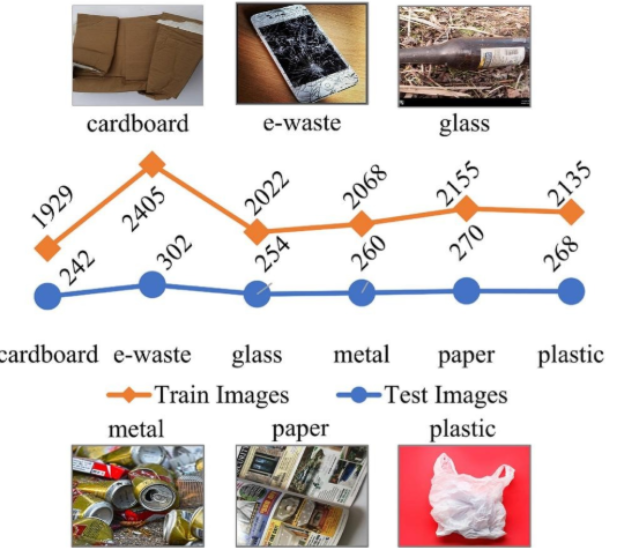

The primary dataset used for testing across the referenced studies is the Kumsetty et al. (2022) waste-image dataset, whose 1,596-image test split serves as the main benchmark for evaluating zero-shot, few-shot, and supervised waste-classification models, including Vision-Language Models (VLMs). This dataset contains 14,310 images categorized into six waste classes—cardboard, e-waste, glass, metal, paper, and plastic—and the test portion is specifically used for zero-shot inference, assessing model accuracy, evaluating generalization, and comparing performance across different learning paradigms.

Figure : Kumsetty et al. waste-image dataset samples & numbers

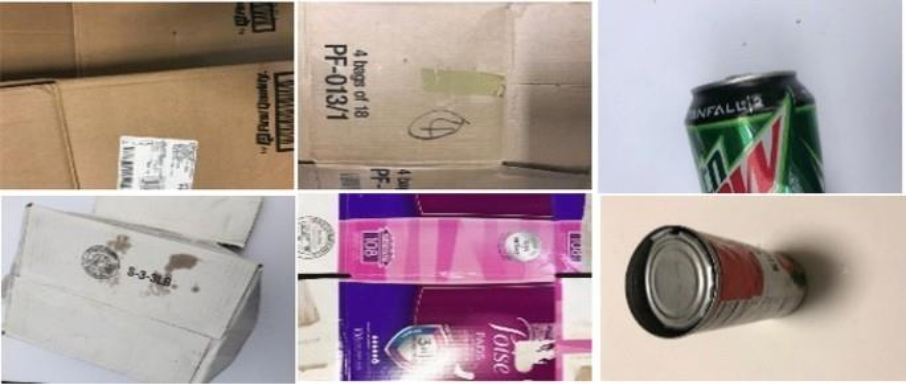

In addition to this central dataset, several related studies report using other datasets for their own testing procedures, though these were not part of the VLM zero-shot evaluation. These include the HUAWEI-40 dataset, comprising 14,683 images across four major waste categories and used to test an enhanced MobileNetV2 classifier; a manually produced dataset based on Stanford Trash/TrashNet with 2,400 manually captured images used to evaluate an ANN-based automated sorting method; and the Yang Trash Dataset (TrashNet), a commonly used benchmark for testing ANN and ResNet-based garbage classification models.

Figure : TrashNet sample

Prospects and Challenges for Real-World Deployment

While Vision-Language Models offer compelling benefits, their real-world deployment requires a balanced view of both opportunities and challenges.

Key Advantages

- Scalability and adaptability: VLMs reduce the heavy reliance on labeled datasets, making it much easier to incorporate new waste categories.

- Computational efficiency: Few-shot and supervised workflows demand far less training time and energy than traditional models.

- High baseline accuracy: Zero-shot capabilities and prompt engineering allow for strong performance even without image-based training.

Practical Challenges

- Prompt engineering workloads: Refining prompts often requires manual iteration and can introduce human bias if not carefully validated.

- Compute constraints: Large VLMs may challenge facilities with limited hardware or edge-computing setups.

- Lack of standard datasets: Without unified waste datasets, benchmarking and cross-system comparisons remain difficult.

- Upfront investment: Even with long-term gains, the initial cost of advanced automated sorting systems remains a barrier for many operators.

Successfully addressing these hurdles will be crucial for widespread adoption.

Conclusion: The Future of Automated Waste Recognition

While conventional unimodal computer vision systems have delivered strong accuracy, their dependence on large, meticulously labeled datasets creates significant bottlenecks. These limitations make it slow and costly for waste management facilities to adapt to evolving waste streams.

Vision-Language Models offer a practical and powerful solution. Their strengths – zero-shot adaptability, efficient supervised learning, and substantial accuracy gains through prompt engineering – directly address the weaknesses of traditional approaches. By bridging images and language, VLMs create more flexible, intelligent, and cost-effective sorting systems.

Ultimately, Vision-Language Models represent a major technological leap forward. Their adaptability and efficiency position them as a foundational tool for building the next generation of automated systems – systems capable of supporting the transition to a truly circular economy.

Further Reads

- AMP Robotics raises $55 million for AI that picks and sorts recyclables : https://venturebeat.com/ai/amp-robotics-raises-55-million-for-ai-that-picks-and-sorts-recyclables

- Automated waste-sorting and recycling classification using artificial neural network and features fusion: a digital-enabled circular economy vision for smart cities: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11042-021-11537-0

- Garbage detection and classification using a new deep learning-based machine vision system as a tool for sustainable waste recycling: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0956053X23001915

- Recent Developments in Technology for Sorting Plastic for Recycling: The Emergence of Artificial Intelligence and the Rise of the Robots: https://www.mdpi.com/2313-4321/9/4/59

- Revolutionizing urban solid waste management with AI and IoT: A review of smart solutions for waste collection, sorting, and recycling: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590123025001069

- Enhancing waste recognition with vision-language models: A prompt engineering approach for a scalable solution: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956053X25003502